What happens when you perform without a conductor? At this year’s Anghiari Festival – and then again in a Free Rush Hour Concert in September – Southbank Sinfonia Associate Leader Eugene Lee takes charge of the orchestra for performances without a conductor.

What happens when you perform without a conductor? At this year’s Anghiari Festival – and then again in a Free Rush Hour Concert in September – Southbank Sinfonia Associate Leader Eugene Lee takes charge of the orchestra for performances without a conductor.

What’s different when you’re leading an unconducted performance?

In essence, the job of the conductor suddenly lies on my shoulders – but I try to share that responsibility with my colleagues in the orchestra. I have to be aware of what’s happening, all the time, everywhere in the ensemble, but hopefully I’ll have colleagues who can fill in any gaps that I might have missed. It becomes even more of a collaborative endeavour.

Do rehearsals without a conductor have a different process or atmosphere?

Yes – personally, I still find it tricky to both lead and ‘conduct’. If I could choose, I’d let go of the playing part a little more and focus on listening for other things happening in the orchestra. It means I need to know my part inside-out, to be able to play it almost by muscle-memory alone, to free up my brain to concentrate on other elements during rehearsals.

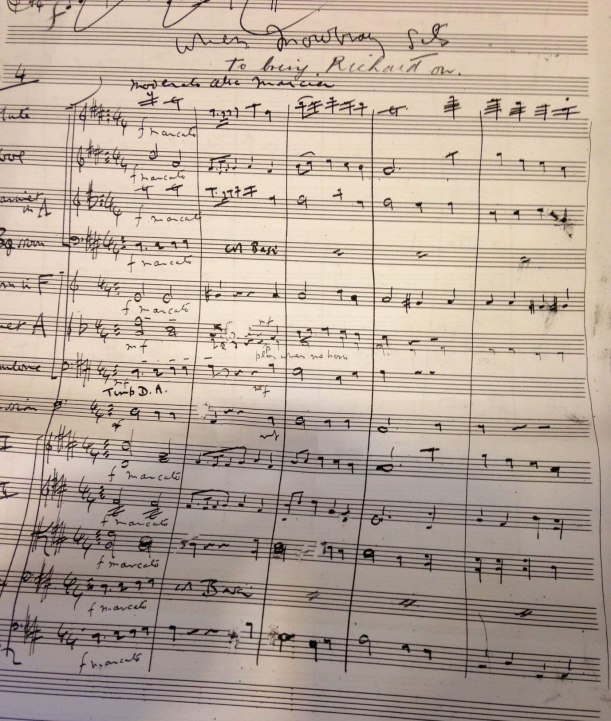

— Eugene directs Philip Glass’ Company at the 2016 Anghiari Festival —

In the same way that a conductor would study a score in advance, is this something you do too?

Absolutely, I’m constantly studying scores for the festival at the moment – and listening to recordings too. In part this helps to generate ideas to bring to the pieces, but it also means that when we come to play them in real-time, my ears will automatically know what they’d like to hear. In a way, that’s the rehearsal process: I have an auto-playback in my mind of what I’d like to hear, and if the live version doesn’t match it then I know that’s an area we need to explore further.

How do you communicate with the orchestra whilst playing?

Ideally, whether we’re performing with or without a conductor, the whole orchestra should be animated – depending on the mood of the piece, of course. Primarily, the communication between us happens aurally, but we do use little gestures to signal certain moments. A lot of eyes are on me as the leader, but I’m always looking for moments to bounce off everyone else too.

There’s definitely a different energy within the orchestra during an unconducted performance. I hope the audience feels it, because on-stage we certainly do. There’s an added challenge that collectively you know is achievable, but requires that much more work to overcome. By the end of an unconducted piece, everyone feels like they’ve contributed something individually, and it’s a great feeling to receive the applause as an ensemble together.

— Back in 2015, we looked at how an orchestra communicates without a conductor as part of a Family Concert —

How are you feeling about your concerts at the 2017 festival?

The first movement of Beethoven’s Fifth is definitely scary unconducted – how do you even start it? It’s only four notes, but it’s a huge technical challenge to get it sounding tight as an ensemble. I’m still thinking about exactly what gesture I could give, or whether there’s some sort of new, secret formula to be found. There’s also a danger that it could sound like any other performance of the symphony, so we’ll try to find something to give it a freshness and new shades of colour.

With Mendelssohn, I’m curious to look deeper into his personality and his uncertainties. The Hebrides is so lonely, as though it’s searching for something… hopefully we can find it.

Eugene leads unconducted performances of works by Mendelssohn, Stephen Hough and Beethoven on Tuesday 25 July in Anghiari.

Back in London, he also leads a Rush Hour of Northern European string music in September. Find out more here.

Eugene was part of Southbank Sinfonia’s 2009 fellowship. Now a member of the Philharmonia Orchestra, he continues to work with Southbank Sinfonia throughout the year as Associate Leader, coaching and mentoring members of the current fellowship.

Alice Thompson

Alice Thompson